I think it would have been nicer if I had written about the places I visited in Japan in the order I visited them and maybe not more than a year after, but there you go. I want to write about one of my favourite places – Nara.

We went to Nara after leaving Osaka, heading for Kyoto, our final destination. We took a train and stopped in Nara. I really liked the train we took and I think that in the two weeks we were in Japan, we took so many trains that I think we covered pretty much all of the types. Of course, the most comfortable is the Shinkansen, way more comfortable than the plane seat, even though we flew Qatar Airways and they really have class. But the train I like the most was the Trans-Kyushu Limited Express that took us to Aso. It was an older type of train and the route it takes is just out a fairy tale. If you have the chance, you should take this train and enjoy the wonderful scenery.

So, coming back to Nara, we only had one day to visit it and Fushimi Inari Taisha wasn’t in the guide’s plan, but some of us really wanted to stop and see as much as we could. About Fushimi Inari Taisha in the next article.

The first permanent capital of Japan was established in the year 710 at Heijo, the city now known as Nara. As the influence and political ambitions of the city’s powerful Buddhist monasteries grew to become a serious threat to the government, the capital was moved to Nagaoka in 784. Nara is located less than one hour from Kyoto and Osaka. Due to its past as the first permanent capital, it remains full of historic treasures, including some of Japan’s oldest and largest temples.

Well, maybe the first thing you notice in Nara are the deers. There are thousands of them. According to local folklore, deer from this area were considered sacred due to a visit from one of the four gods of Kasuga Shrine, Takenomikazuchi-no-mikoto. He was said to have been invited from Kashima, Ibaraki] and appeared on Mt. Mikasa-yama riding a white deer. From that point, the deer were considered divine and sacred by both Kasuga Shrine and Kōfuku-ji.Killing one of these sacred deer was a capital offense punishable by death up until 1637, the last recorded date of a breach of that law. After World War II, the deer were officially stripped of their sacred/divine status, and were instead designated as National Treasures and are protected as such. You can buy special crackers to feed the deers, but they have no problem searching your pockets, your bag, whatever is more handy.

To me, they looked really sad. But anyway, they really are not scared of humans, after so long and are truly used to the modern ways:

though they can be pretty insistent when asking for food, so it would be better if you don’t annoy them, or else:

First, we went here on our way to Tōdai-ji. It was really really crowded, but the trees were in full bloom and it was one of the rare sunny and warm days we had, so everything was beautiful.

We didn’t go inside the temple, saw only the front yard because as usual, we were “on the run”.

Tōdai-ji - Eastern Great Temple - is a Buddhist temple complex. Its Great Buddha Hall - Daibutsuden - houses the world’s largest bronze statue of the Buddha Vairocana, known in Japanese simply as Daibutsu. The temple also serves as the Japanese headquarters of the Kegon school of Buddhism. The temple is a listed UNESCO World Heritage Site as “Historic Monuments of Ancient Nara”, together with seven other sites including temples, shrines and places in the city of Nara.

The beginning of building a temple where the Tōdai-ji complex sits today can be dated to 728, when Emperor Shōmu established Kinshōsen-ji as an appeasement for Prince Motoi, his first son with his Fujiwara clan consort Kōmyōshi. Prince Motoi died a year after his birth.

During the Tenpyō era, Japan suffered from a series of disasters and epidemics. It was after experiencing these problems that Emperor Shōmu issued an edict in 741 to promote the construction of provincial temples throughout the nation. Tōdai-ji (still Kinshōsen-ji at the time) was appointed as the Provincial temple of Yamato Province and the head of all the provincial temples. With the alleged coup d’état by Nagaya in 729, an outbreak of smallpox around 735–737, worsened by consecutive years of poor crops, then followed by a rebellion led by Fujiwara no Hirotsugu in 740, the country was in a chaotic position. Emperor Shōmu had been forced to move the capital four times, indicating the level of instability during this period.

In 743, Emperor Shōmu issued a law in which he stated that the people should become directly involved with the establishment of new Buddha temples throughout Japan. His personal belief was that such piety would inspire Buddha to protect his country from further disaster. Gyōki, with his pupils, traveled the provinces asking for donations. According to records kept by Tōdai-ji, more than 2,600,000 people in total helped construct the Great Buddha and its Hall. The 16 m (52 ft) high statue was built through eight castings over three years, the head and neck being cast together as a separate element. The making of the statue was started first in Shigaraki. After enduring multiple fires and earthquakes, the construction was eventually resumed in Nara in 745,[8] and the Buddha was finally completed in 751. A year later, in 752, the eye-opening ceremony was held with an attendance of 10,000 people to celebrate the completion of the Buddha. The Indian priest Bodhisena performed the eye-opening for Emperor Shōmu. The project nearly bankrupted Japan’s economy, consuming most of the available bronze of the time.

The original complex also contained two 100 m pagodas, perhaps second only to the pyramids of Egypt in height at the time. These were destroyed by earthquake. The Shōsōin was its storehouse, and now contains many artifacts from the Tenpyo period of Japanese history.

This is the imposing Nandaimon, the Great Southern Gate, just wanted you to see how small the man in the centre of the picture is compared to it. The existing Nandaimon is a reconstruction of end-12th century based on Song Dynasty style.

And the flag, so the pack wouldn’t get lost:

Then you have the guardians:

And so you’ll get an idea of how big they are:

The dancing figures of the Nio, the two 28-foot-tall guardians at the Nandaimon, were built at around the same time by Unkei, Kaikei and their workshop members. The Nio are an A-un pair known as Ungyo, which by tradition has a facial expression with a closed mouth, and Agyo, which has an open mouthed expression. The two figures were closely evaluated and extensively restored by a team of art conservators between 1988 and 1993. Until then, these sculptures had never before been moved from the niches in which they were originally installed. This complex preservation project, costing $4.7 million, involved a restoration team of 15 experts from the National Treasure Repairing Institute in Kyoto.

The next gate you have to pass:

And then you see it:

The gardens that surround it:

The Great Buddha Hall (Daibutsuden) has been rebuilt twice after fire. The current building was finished in 1709, and although immense—57 m long and 50 m wide—it is actually 30% smaller than its predecessor. Until 1998, it was the world’s largest wooden building. It has been surpassed by modern structures, such as the Japanese baseball stadium ‘Odate Jukai Dome’, amongst others. The Great Buddha statue has been recast several times for various reasons, including earthquake damage. The current hands of the statue were made in the Momoyama Period (1568–1615), and the head was made in the Edo period (1615–1867).

This left me breathless. It wasn’t just the size of the statue, but also the atmosphere in this place, it was so warm and peaceful even though there was an amazing numer of people. I found a nice bench in a corner and just sat there with my eyes closed, just feeling that incredible space.

Several smaller Buddhist statues and models of the former and current buildings are also on display in the Daibutsuden Hall. Another popular attraction is a pillar with a hole in its base that is the same size as the Daibutsu’s nostril. It is said that those who can squeeze through this opening will be granted enlightenment in their next life.There were more statues in the temple:

By the way, I bought more bells here. :D Yes, I know, I’m a maniac, but I just love their sounds. I think I bought 5, but I gave 2 as presents, so I was left with just 3. :D (Oh, and I bought more – different models in Beppu and Miyajima. I’ll take a picture of them someday and show them to you.)

I was so sorry we only had half an hour to admire this unique place, next time, I’ll stay at least an hour. And now, on to Kasuga Taisha - Nara’s most celebrated Shinto shrine. It was established at the same time as the capital and is dedicated to the deity responsible for the protection of the city. Kasuga Taisha was also the tutelary shrine of the Fujiwara, Japan’s most powerful family clan during most of the Nara and Heian Periods. Like the Ise Shrines, Kasuga Taisha had been periodically rebuilt every 20 years for many centuries. In the case of Kasuga Taisha, however, the custom was discontinued at the end of the Edo Period.

Beyond the shrine’s offering hall, which can be visited free of charge, there is a paid inner area which provides a closer view of the shrine’s inner buildings. Furthest in is the main sanctuary, containing multiple shrine buildings that display the distinctive Kasuga style of shrine architecture, characterized by a sloping roof extending over the front of the building.

Kasuga Taisha is famous for its lanterns, which have been donated by worshipers. Hundreds of bronze lanterns can be found hanging from the buildings, while as many stone lanterns line its approaches. The lanterns are lit twice a year on the occasion of the Lantern Festivals in early February and mid August.

And this is where we separated as a group and we each went our separate ways, settled to meet at a certain hour at the train station. I went with two sisters that were on the same visit as much as possible lenght as me.

And we came across Kōfuku-ji - The Five Storied Pagoda which is a National Treasure. The temple is the national headquarters of the Hossō school and is one of the eight Historic Monuments of Ancient Nara inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Kōfuku-ji has its origin as a temple that was established in 669 by Kagami-no-Ōkimi, the wife of Fujiwara no Kamatari, wishing for her husband’s recovery from illness. Its original site was in Yamashina, Yamashiro Province (present-day Kyoto). In 672, the temple was moved to Fujiwara-kyō, the first planned Japanese capital to copy the orthogonal grid pattern of Chang’an. In 710 the temple was dismantled for the second time and moved to its present location, on the east side of the newly constructed capital, Heijō-kyō, today’s Nara.

Kōfuku-ji was the Fujiwara’s tutelary temple, and enjoyed as much prosperty, and as long as the family did. The temple was not only an important center for the Buddhist religion, but also retained influence over the imperial government, and even by “aggressive means” in some cases.When many of the Nanto Shichi Daiji such as Tōdai-ji -declined after the move of capital to Heian-kyō (Kyoto), Kōfuku-ji kept its significance because of its connection to the Fujiwara. The temple was damaged and destroyed by civil wars and fires many times, and was rebuilt as many times as well, although finally some of the important buildings, such as two of the three golden halls, the nandaimon, chūmon and the corridor were never reconstructed and are missing today.

And around it, there is this:

And then, there I am, about to east something really good with chestnuts.

And we went walking and also did some shopping. We found the most wonderful store selling antiques. I bought a really nice bowl for my exboyfriend because he loves antiques and for me I found these very cute bowls, I bought three for 100 Yen each which is a real bargain, I practically felt I got them as a gift. And just so you’ll have an idea about the prices, my ex’s bowl cost a few thousand Yen compared to my 100 Yen. The friends I was with bought dolls, beautifully made. I think we browsed that store for more than 40 minutes.

The store had an outside display too and as I was browsing, I saw them and quickly took a photo.

We also stumbled on a Koto concert. The Koto is national instrument of Japan. Koto are about 180 centimetres (71 in) length, and made from kiri wood (Paulownia tomentosa). They have 13 strings that are strung over 13 movable bridges along the width of the instrument. Players can adjust the string pitches by moving these bridges before playing, and use three finger picks (on thumb, index finger, and middle finger) to pluck the strings.

Continuing to the train station

Nara is a city in which you absolutely have to stay for more than a day as we did. There are so many things to see and it’s just a very beautiful place with an air that to me, spoke of the old Japan, a place where you can really feel history unfolding.

This is the train we took to Fushimi Inari Taisha. Till the next article, I leave you with this image.

Showing posts with label Japan. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Japan. Show all posts

Friday, September 6, 2013

Nara

Labels:

architecture,

Daibutsuden,

deer,

history,

Japan,

Japanese lanterns,

Kasuga-Taisha,

Kōfuku-ji,

Koto,

Nara,

sakura,

spring,

temples,

The Five Storied Pagoda,

Todai-ji,

UNESCO,

wood

Thursday, May 2, 2013

Japanese Musical Instruments - The Shamisen

Kitagawa Utamaro, “Flowers of Edo: Young Woman’s Narrative Chanting to the Samisen”

The shamisen or samisen, also called sangen, is a three-stringed, Japanese musical instrument played with a plectrum called a bachi.

The shamisen had many forms before it arrived to Japan, though it’s unclear where it originated from. It is said that a three stringed lute arrived in China during the later years of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). This instrument is called the sanxian. Trade flourished between China and the Ryukyu kingdom (Okinawa). Many instruments were brought over, including their sanxian, now called the Okinawan Sanshin. It is said to have been brought over by merchants from Fukien in 1392, a time when there was considerable immigration from southern China.

The Sanxian

Now we come to it’s arrival to Japan. It’s generally said that the sanshin came to Japan in 1562, in the city of Sakai (a port city south of Osaka). It’s assumed to have come from Okinawa, though with all the trade that was happening with China, direct importation was by no means out of the question. There probably were Chinese sanxian in Japan before 1562, but not in significant enough numbers to start anything. The Okinawan sanshin is what caused the shamisen to be taken up by the Japanese.

Soon after, biwa players took up the sanshin (now called the shamisen) so they could be better heard on the street. And being the first players of the instrument in Japan, they could do what they wanted with it! And do they did.

Soon after, biwa players took up the sanshin (now called the shamisen) so they could be better heard on the street. And being the first players of the instrument in Japan, they could do what they wanted with it! And do they did.

Kusakabe Kimbei - Geshia Playing Shamisen

The shamisen is a plucked stringed instrument. Its construction follows a model similar to that of a guitar or a banjo, with a neck and strings stretched across a resonating body. The neck of the shamisen is fretless and slimmer than that of a guitar or banjo. The body, called the dō , resembles a drum, having a hollow body that is taut front and back with skin, in the manner of a banjo. The sao, or neck of the shamisen is usually divided into three or four pieces that fit and lock together. Indeed, most shamisen are made so that they can be easily disassembled and stowed to save space. The neck of the shamisen is a singular rod that crosses the drum-like body of the instrument, partially protruding at the other side of the body and there acting as an anchor for the strings. The pegs used to wind the strings are long, thin and hexagonal in shape. They were traditionally fashioned out of ivory, but as it has become a rare resource, they have been recently fashioned out of other materials, such as various kinds of wood and plastic.

The three strings are traditionally made of silk, or, more recently, nylon. Traditionally, silk strings are used. However, silk breaks easily over a short time, so this is reserved for professional performances. Students often use nylon or ‘tetron’ strings, which last longer than silk, and are also less expensive.

The three strings are traditionally made of silk, or, more recently, nylon. Traditionally, silk strings are used. However, silk breaks easily over a short time, so this is reserved for professional performances. Students often use nylon or ‘tetron’ strings, which last longer than silk, and are also less expensive.

Shamisen maker with a customer

The shamisen can be played solo or with other shamisen, in ensembles with other Japanese instruments, with singing such as nagauta, or as an accompaniment to drama, notably kabuki and bunraku. Both men and women traditionally played the shamisen.

The most famous and perhaps most demanding of the narrative styles is gidayū, named after Takemoto Gidayū (1651–1714), who was heavily involved in the bunraku puppet-theater tradition in Osaka. The gidayū shamisen and its plectrum are the largest of the shamisen family, and the singer-narrator is required to speak the roles of the play, as well as to sing all the commentaries on the action. From the 19th century female performers known as onna-jōruri or onna gidayū also carried on this concert tradition.

The most famous and perhaps most demanding of the narrative styles is gidayū, named after Takemoto Gidayū (1651–1714), who was heavily involved in the bunraku puppet-theater tradition in Osaka. The gidayū shamisen and its plectrum are the largest of the shamisen family, and the singer-narrator is required to speak the roles of the play, as well as to sing all the commentaries on the action. From the 19th century female performers known as onna-jōruri or onna gidayū also carried on this concert tradition.

Two geishas playing the shamisen

Music for the shamisen can be written in Western music notation, but is more often written in tablature notation. While tunings might be similar across genres, the way in which the nodes on the neck of the instrument (called tsubo) are named is not. As a consequence, tablature for each genre is written differently.

Vertical shamisen tablature, read from right to left. Nodes for the 3rd string are indicated by Arabic numerals, for the 2nd string by Chinese numerals, and for the 1st string by Chinese numerals preceded by イ.

The shamisen is played and tuned according to genre. The nomenclature of the nodes in an octave also varies according to genre. In truth, there are myriad styles of Shamisen across Japan, and tunings, tonality and notation vary to some degree. Three of the most commonly recognized tunings across all genres are “honchoshi” (本調子), “ni agari” (二上がり), and “san sagari” (三下がり).

The construction of the shamisen varies in shape and size, depending on the genre in which it is used. The bachi used will also be different according to genre, if it is used at all. Shamisen are classified according to size and genre. There are three basic sizes; hosozao, chuzao and futozao. Examples of shamisen genres include nagauta, jiuta, min’yo, kouta, hauta, shinnai, tokiwazu, kiyomoto, gidayu and tsugaru.

In most genres the shamisen, the strings are plucked with a bachi. The sound of a shamisen is similar in some respects to that of the American banjo, in that the drum-like dō, amplifies the sound of the strings. As in the clawhammer style of American banjo playing, the bachi is often used to strike both string and skin, creating a highly percussive sound. In kouta ( literally “small song”) style shamisen, and occasionally in other genres, the shamisen is plucked with the fingers.

The construction of the shamisen varies in shape and size, depending on the genre in which it is used. The bachi used will also be different according to genre, if it is used at all. Shamisen are classified according to size and genre. There are three basic sizes; hosozao, chuzao and futozao. Examples of shamisen genres include nagauta, jiuta, min’yo, kouta, hauta, shinnai, tokiwazu, kiyomoto, gidayu and tsugaru.

In most genres the shamisen, the strings are plucked with a bachi. The sound of a shamisen is similar in some respects to that of the American banjo, in that the drum-like dō, amplifies the sound of the strings. As in the clawhammer style of American banjo playing, the bachi is often used to strike both string and skin, creating a highly percussive sound. In kouta ( literally “small song”) style shamisen, and occasionally in other genres, the shamisen is plucked with the fingers.

In the early part of the 20th century, blind musicians, including Shirakawa Gunpachirō (1909–1962), Takahashi Chikuzan (1910–1998), and sighted players such as Kida Rinshōei (1911–1979), evolved a new style of playing, based on traditional folk songs (“min’yō”) but involving much improvisation and flashy fingerwork. This style – now known as Tsugaru-jamisen, after the home region of this style in the north of Honshū – continues to be relatively popular in Japan. The virtuosic Tsugaru-jamisen style is sometimes compared to bluegrass banjo.

Kouta (小唄) is the style of song learned by geisha and maiko. Its name literally means “small” or “short song,” which contrasts with the music genre found in bunraku and kabuki, otherwise known as nagauta (long song).

Jiuta (地唄), or literally “earthen music” is a more classical style of shamisen music.

One contemporary shamisen player, Takeharu Kunimoto, plays bluegrass music on the shamisen. Another player using the Tsugaru-jamisen in non-traditional genres is Michihiro Sato, who plays free improvisation on the instrument. Japanese American jazz pianist Glenn Horiuchi played shamisen in his performances and recordings. A duo popular in Japan known as the Yoshida Brothers developed an energetic style of playing heavily influenced by fast aggressive soloing that emphasizes speed and twang; which is usually associated with rock music on the electric guitar. Japanese traditional and jazz musician Hiromitsu Agatsuma incorporates a diverse mix of genres into his music. He arranged several jazz standards and other famous western songs for the shamisen on his latest album, Agatsuma Plays Standards.Kouta (小唄) is the style of song learned by geisha and maiko. Its name literally means “small” or “short song,” which contrasts with the music genre found in bunraku and kabuki, otherwise known as nagauta (long song).

Jiuta (地唄), or literally “earthen music” is a more classical style of shamisen music.

Labels:

history,

Japan,

Japanese music instruments,

Shamisen

Friday, November 16, 2012

Wagasa - the traditional Japanese umbrella

Wagasa 「和傘」, the traditional Japanese umbrella made from bamboo and washi (Japanese paper), is renowned not only for its beauty but also for the precision open/close mechanism.

The first folding umbrellas appeared in Japan around the year 1550

(before that, the only defense against rain were straw hats and capes)

and they were initially luxury items. Later during the Edo period, wagasa

became more accessible and people started using it not only for

protection against rain or sun but also as a fashion accessory. Many ukiyo-e and vintage photos from Japan show women dressed in kimono assorted with matching wagasa.

Actually, wagasa is so popular in the Japanese tradition that it has its own… spirit. This is Tsukumogami, a kind of Japanese spirit said to appear from an object after 100 years, when… it becomes alive. The spirit of wagasa is called Karakasa Obake, umbrella ghost, a monster looking like a folded wagasa, with a single eye and a single foot wearing a geta.

Still known today as a center for the production of traditional

Japanese umbrellas, manufacture of wagasa began in the Kano district

of Gifu City in the middle of the 18th century. At that time, the state

had feudal organization and the local lords had a great deal of economic

and political autonomy within the domains to which they were assigned.

The feudal lord who was transferred in to rule the feudal domain around

Gifu had to contend with a local economy that was devastated by floods.

He saw an opportunity to stimulate local industry and to provide the means

to supplement the living of the impoverished lower samurai (warrior elite)

by encouraging them to make umbrellas.

The local area had a long history of paper making. Mino-washi,

a local product, which was a strong handmade paper due to the long fibers it

contained. Good quality bamboo was to be found in the valley of the Kiso

River, and it was easy to obtain sesame oil and lacquer from the local

mountains, indispensable for water proofing. These advantages made the

area well suited for umbrella making, since the basic construction of Japanese

umbrellas involves affixing paper over a frame of bamboo-strip ribs, and

then applying oil and lacquer for waterproofing.

Production peaked at the beginning of the 20th century,

when over a million umbrellas per year were manufactured. Since then, the

metal-and-cloth Western-style umbrella has become generally used, and the

number of people who use Japanese umbrellas has dwindled. These days, the

local craftworkers make only few tens of thousands of wagasa a year.

The traditional Japanese umbrella uses only natural materials

and, requiring several months to undergo the various separate processes

that are needed for completion, the skilled hands of a dozen seasoned craftworkers

contribute to the finished item. In addition to the usual type of rain

umbrella, Gifu Wagasa also comes in various other types including large

red outdoor parasols that are used to provide shade on outdoor occasions,

such as tea ceremonies.

Then there are smaller colorful buyo-gasa that figure in performances

of traditional

Japanese dance. Gifu Wagasa are an indispensable part of traditional

Japanese art and culture.

Wagasa’s paper is coated with oil to make it waterproof and at the same

time, the coated paper becomes more solid. On the contrary, some Wagasa

parasols are not coated with oil and thus they cannot be used during

rainy days but only as protection from the sun.

The Bangasa umbrellas are usually bigger and thicker, with more ribs and

they tend to be heavier, so they are mostly used by men. The colors are

also simpler. However, there are no restrictions and women can also use

Bangasa. Another type of Wagasa is the Janome Kasa, which on the contrary have less ribs and are lighter while colors can be very varied. These

are mostly used by women.

The production process of Wagasa is completely handmade and takes a long time:

- Prepare the material (bamboo, Washi paper, lacquer…)

- Build the frame around a wooden core to create the structure

- Match the size of the Washi paper to the structure

- Attach the paper covering to the bamboo structure with glue and let it dry

- Painting and lacquering of the Washi paper

- Coating of the paper with linseed oil to make it waterproof

- Drying of the coating which can vary from 4 to 15 days

- Threads stitching and final decoration

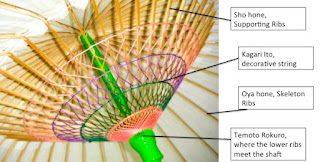

Each part of a Japanese umbrella has a name and a function. For

instance, the Nokizume (see picture below) are the parts of the ribs

sticking out from the umbrella. These are often lacquered in red because

of an ancient Japanese tradition. Indeed, at the beginning the very

first umbrellas were only used by the Imperial family and aristocrats

and they were said to be magical objects that could protect one from evil

spirits and bad events and from this belief came the color red that was

said to help prevent bad things from happening.

To preserve your Wagasa and insure its longevity you should store it

untied and loosened in a well ventilated, dark place. It is also important

to dry it well, for instance with a towel, after using it. It is best

to let it open in a dark place until it is completely dry. Once dry, you

can close it loosely and store it in a dark, well-ventilated place.It

is important to not let the Wagasa in the sun to dry since the colors

and patterns might tarnish.

Finally, it is possible to have your Wagasa umbrella repaired but,

depending on its state, the reparation cost might be higher than the

cost of a new umbrella. The number of artisans being able to do this

reparation is also very limited. When the ribs of the umbrella are

broken, it is then impossible to repair.

The western type of umbrella was brought to Japan during the Meiji period and, over time, completely replaced the wagasa, because of the higher resistance and much lower costs.

However, there are still several workshops producing wagasa in Gifu, Kyoto, Ishikawa, Tottori and Tokushima and wagasa is still used in traditional activities like tea ceremony, kabuki theater, Japanese dances or festivals.

However, there are still several workshops producing wagasa in Gifu, Kyoto, Ishikawa, Tottori and Tokushima and wagasa is still used in traditional activities like tea ceremony, kabuki theater, Japanese dances or festivals.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)